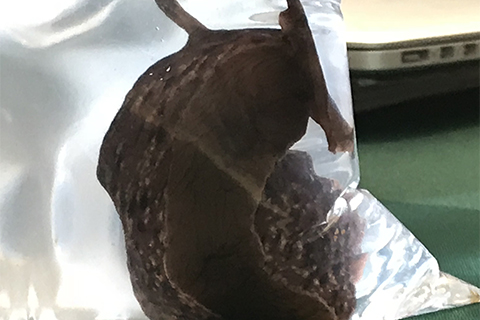

For all the meekness of its name, the sea hare moves with a pretty tough crowd. Toxic really. It will immobilize your heart within seconds if you’re hit with a dart of venom blasted like a harpoon hook by the blue-ringed octopus, flamboyant cuttlefish, predatory snail, or fluorescent nubibranch—all mollusk pals of the Aplysia californica, or sea hare.

Yet much in the same way that we might better understand human behavior from gangstas and street toughs, we can learn—and have been learning for decades—how memory and learning take place by researching the sea hare and his/her (many of them are hermaphroditic) maritime thugs.

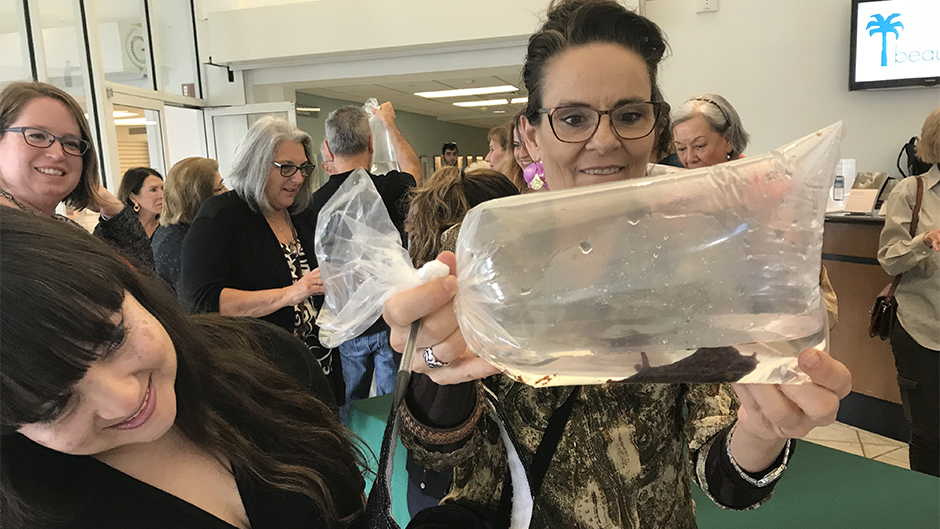

“What the Sea Hare Can Teach Us about Our Brains” was the subject of Lynne Fieber’s talk November 30 at the University of Miami's Lowe Art Museum. Fieber, an associate professor with UM’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (RSMAS) Department of Marine Biology and Ecology, has been studying these quirky gastropods since 1990.

These mollusks (snails, slugs) with a distinct head bearing sensory organs that inhabit the swirling sea world (and the petri dishes in Fieber’s lab at RSMAS) have been highly instructive in helping us understand human learning and memory.

“We use animal models such as the California Sea Hare (native to the Pacific Ocean) for experiments because their simple nervous systems can teach us about our more complex nervous system,” Fieber said, explaining “if you could touch its ‘fingers’ to a hot stove there would be only a few nerve cells that would engage, in contrast with the tens of thousands of nerve cells in humans.”

According to Fieber, the value of sea hare research rests on three pillars: simple, tractable, and faithful. “Simple” because the physiology of their nervous systems replicates ours, though in a far simpler way. “Tractable” because we can make accurate associations and comparisons, and “faithful” because, when removed, their nerve cells provide the same results again and again when tested.

For decades, the scientific world probed and pondered the question: If memory were something you could hold in your hand, what would it be? While no one could say definitively what learning and memory were, several hypotheses moved closest to answering the query: one, that learning was associated with a bioelectrical field or “aura” in the brain, and two, that a special point of contact, a synapse, between cells was key. In other words, if connections got stronger, learning was occurring; if the connection weakened, then learning or information was being lost, as with an Alzheimer's or dementia condition.

Sea hare research by Fieber and others tipped the scale in favor of the latter explanation: the strength or weakness of a synaptic connection is now accepted as the accurate basis for understanding how learning and memory, both short-term and long-term, occur.

“It’s the same thing in us—and unbelievably exciting to be associated with,” says Fieber, adding “we found out long ago that they are capable of learning, of both initiating and demonstrating learning.”

Scientists Arvid Carlsson, Paul Greengard and Eric Kandel, in fact, were awarded the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology for their discoveries concerning “signal transduction in the nervous system” and stemming from understanding these same synapses.

Fieber’s research team has monitored how touching the tail of a young sea hare prompts a vigorous response of “fear, whoa, something wrong.” A few minutes later, there is a somewhat less vigorous response, and then increasingly less, as the animal begins to “learn” that the touch is not harmful. A more mature sea hare will have an initial “ho-hum” response to the touch, indicating how its sensory “brain” has slowed with aging.

Fieber’s research team has monitored how touching the tail of a young sea hare prompts a vigorous response of “fear, whoa, something wrong.” A few minutes later, there is a somewhat less vigorous response, and then increasingly less, as the animal begins to “learn” that the touch is not harmful. A more mature sea hare will have an initial “ho-hum” response to the touch, indicating how its sensory “brain” has slowed with aging.

Fieber teaches classes on marine invertebrates and an introduction to marine science that allows first-year RSMAS students to literally immerse themselves in their chosen major.

The lunchtime presentation at the Lowe Art Museum was offered in association with the Into the Mysterium exhibit by Michele Oka Doner, known for her public art commissions. The collection of 55 large-format photographs of specimens from the RSMAS Marine Invertebrate Museum and an immersive four-channel video installation, Mysterium Alive, runs through January 14, 2018.